Speakers for the ANPSA Blooming Biodiversity Conference have been selected, and a preliminary listing is now available on our website here. It will be an exciting Conference, with more details to be released in the near future.

Category: Science matters

Plant ID Workshop Success

‘What a fantastic workshop! Would have to be the best $20 I’ve ever spent!’ – these are comments from participants of the Eastern Hills Branch two day workshop on plant identification, led by botanists Janet Atkins and Penny Hussey, who taught the anatomy of plants and then went through a collection of plant families and their characteristics. What an amazing benefit of being a member of the Society. Many thanks EH Branch, and Janet and Penny.

We’re on Gardening Australia

Josh Byrne visits the Helen and Aurora Range with WA Wildflower Society member Brian Moyle, who has spent many years working to protect this rare banded-ironstone landscape and its Gimlet gum (Eucalyptus salubris) woodland. It is currently within a conservation park, but the Society is hoping to have it changed to a National Park due to its National Heritage values. The view from the summit is breathtaking.

The hard, hot rock formations result in temperature extremes, ranging from 50 degrees to freezing. The area has produced many species that occur nowhere else in the world, such as the Bungalbin tetratheca (Tetratheca aphylla), which produces masses of purple flowers in spring and grows in tiny cracks in the rock. We also see the ironstone beard-heath (Leucopogon spectabilis), which has white flowers and seemingly grows straight out of the rock!

Link to video here: http://www.abc.net.au/gardening/factsheets/remote-ranges/10343146

Arborescence – making a tree

What is Arborescence? Arborescence is the term used to describe a plant as “tree-like”. And there are many plants that are arborescent , pines, eucalyptus, balga’s, palms and tree ferns to name a few. Plants like pines and eucalyptus are what fall into the “correct” definition of a tree.

To begin at basics a plant will grow by creating “primary growth” which makes the phloem and xylem that we are familiar with. A “tree” goes a step further by producing what is called secondary growth from the vascular cambium layer, although it looks more like a ring in cross section. What this means is that secondary phloem and xylem is created, thickening and widening the stem.

Other plants however also achieve arborescence without using a cambium layer. Monocots like Xanthorrhoea, Pandanus and the palm family achieve this by different methods.

1. Thick persistent leaf bases seen in Xanthorrhoea are one solution, by allowing your leaf bases to take the main support role this overcomes the need for a cambium layer.

2. Pandanus achieve arborescent status by growing prop roots to support an expanding canopy.

3. The palm family Arecaeae, the most famous arborescent monocots use a different method, they use secondary thickening. But not from a single cambium layer. Rather the parenchyma cells within individual vascular bundles do. This is called anomalous secondary growth.

Now within the ferns there are two primary methods.

1. The first is by strengthening the internal stem with hard sclerenchyma, this hardened tissue runs lengthways through the stem.

2. The second method is by the growth of special fibrous, interlocking roots called a Root Mantle. These roots can grow all up the stem and is widest at the base. An extinct tree fern species called Tempskya relied entirely upon it’s root mantle, reaching heights of 6m. This reliance on the root mantle also gave the plant a peculiar appearance (as seen above).

3. Finally ferns also use persistent leaf bases.

Now we might think that is the end of it, but wait. I found another method used by the now extinct lepidodendrids. Lepidodendrids could grow as high as 55m and have a trunk diameter of 2m. they gained arborescence by enlarging and thickening their outer bark layer.

So there you have it all of the methods (that I could find) of becoming arborescent.

References

Moran, R,C. 2004. A Natural history of Ferns, Timber Press INC. London

https://florabase.dpaw.wa.gov.au/browse/profile/22740

https://florabase.dpaw.wa.gov.au/browse/profile/22753

http://xfrog.com/product/PR18.html

Darling Range NatureBase

Members of the Darling Range Branch of the Wildflower Society and the Naturalists Club have coordinated with Michael and Lesley Brooker to produce a ‘Darling Range Naturebase’ document which is a guide to plants and animals to be found in the area. You are free to download this wonderful reference guide at https://lesmikebrooker.com.au/Darling-Range-NatureBase.php or link here. For more information about Darling Range Branch of the Wildflower Society, check out their page here.

Bush Heritage says ‘thanks’

Wonderful blog from Bush Heritage thanking the Wildflower Society for conducting flora surveys at Hamelin Station and Eurardy Station. We had a lot of fun doing the work… and it is our pleasure. And how nice to receive public recognition.

‘We now have over 50 Threatened, Priority and/or endemic plant species on the list for Eurardy Reserve – amazing! Our most recent purchase in the Mid-west – Hamelin Station Reserve – is located next to the Shark Bay World Heritage Area and had never been surveyed in detail for flora.’ -Vanessa Westcott, Bush Heritage Ecologist

Read the blog here: https://www.bushheritage.org.au/blog/the-wonderful-wildflower-society-of-wa

Photo courtesy Bush Heritage

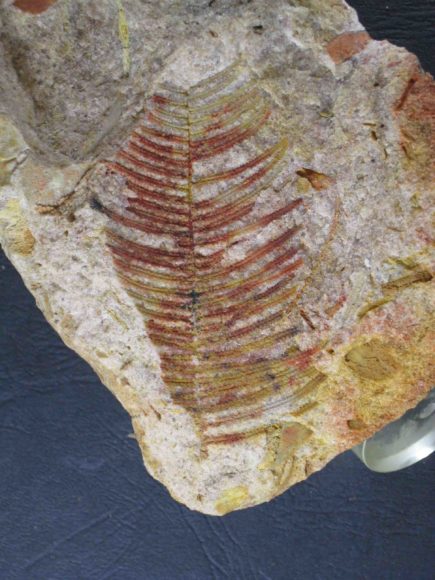

Western Australian Fossil Plants and Climate

Dr Ken McNamara, University of Cambridge was guest speaker for Armadale Branch meeting in April 2017.

Ken began his talk by stressing the importance of looking at the nature of rocks and fossil plants in helping to understand past climates. In particular they have helped show that over the last half a billion years, the Earth has experienced long periods of alternating ‘Greenhouse’ and ‘Icehouse’ worlds. During the former, CO2 levels and global temperature were much higher than in the current ‘Icehouse’ world we inhabit.

Ken’s talk centred on two fossil plant sites, both of which have only received preliminary studies. One, dated at about 130 million years old (Cretaceous Period) is near Kalbarri. The other, about 40 million years old, is at Walebing, east of Moora. They are very different from one another in that the older site near Kalbarri contains plants living before the advent of flowering plants. The fossils show that the area was dominated by ferns (about 40% of the flora), including gleicheniacean, dipteridacean and osmundacean types. The rest of the flora was mainly arauraciacean conifers (25%) and an extinct group, the seed ferns (25%). The rest are forms yet to be identified. Some of the seed ferns are similar to fossils found in India, which was close to Australia at this time. While much of the fossil plant material is leaves and broken branches, there are a number of seeds and also frequent seed scales from the conifers.

Like this Cretaceous flora, the younger 40 million-year-old (Eocene Epoch) Walebing site preserves the fossils as impressions in very silicified sandstones. These rocks are known as silcretes and reflect formation at a time when the climate was much wetter and warmer than today, despite being located at much higher latitudes than now (55°–60°), with pronounced seasonality. The fossils are very common and reflect a very diverse flora, dominated by proteaceans, such as banksia, grevillea and possibly macadamia. The very diverse array of banksia leaf types show biodiversity levels were high even at this time, and probably had been on the nutrient-poor soils for tens of millions of years before, back into late Cretaceous times.

As well as these sclerophyllous plants the flora also contains rainforest elements, such as the Southern Antarctic beech, Nothofagus and many myrtaceous leaves that resemble modern rainforest types. Araucareaceans are still present, as well as casuarina-type fruiting bodies, including some types present today only in rainforests in eastern Australia and New Caledonia.

Study of the leaves of one of the banksia species, B. paleocrypta, shows that it has sunken stomata, suggesting that it was preadapted for the drying out of the Australian continent that has occurred over the last 25 million years or so. The rainforest elements have disappeared from WA, leaving only those forms, such as the proteaceans, that were preadapted to both the nutrient-deficient soils and the seasonal periods of low water availability.

In his closing comments, Ken pointed out that much more work needs to carried out on these floras. This will help provide a better understanding of the evolution of the rich flora that we see in Western Australia today.

Be Awarded, Be Connected – Student Prize Winners.

The student prizes are one of many ways we as a society try to bridge the inter-generational gap. And the older folks have a lot to share, believe me!

Perth Branch is supporting UWA students; Northern Branch is looking at ECU while Murdoch Branch is obviously looking for the best students around its own bush that is Murdoch University and TAFE Challenger.

Last two years Murdoch Branch had a great honour to award four outstanding people. Pawel – our (tall) president of the last two years (2015-2016) is very happy to hand over the awards to:

1. Merryn – the best student in “Plant Diversity” in 2015:

Continue reading “Be Awarded, Be Connected – Student Prize Winners.”

Talk by Michael Morcombe on Pollination

Prior to the business meeting, the guest speaker for the evening was fellow member Michael Morcombe, whose topic was Pollination in an isolated region outlining the diverse and unique tactics by plants, insects, birds and mammals.

Michael explained briefly how he became interested in this field by explaining that he was asked to write a book in which pollination was a part,but couldn’t actually find anything on pollination in the southern hemisphere in the university library. This began a long and interesting journey recording just how plants are pollinated in Australia resulting in many long road trips for his family and a lifelong interest in photographing their finds for Irene.

We have a unique flora here in Western Australia,so Michael showed some wonderful slides, many taken by Irene, of how the plants use insects, birds and mammals to help them with their pollination. Plants have adapted to be insect-pollinated and many have long tubes which cover the insects in pollen. Insects can see ultra-violet light and so what looks like a plain flower to the human eye actually shows a pathway to the nectar through the insects’ eyes. Generally insects are attracted to blue/purple/white flowers while birds are attracted to red/yellow flowers.

Orchids are very clever and have evolved to play tricks on insects. Many have parts which mimic female wasps and the orchid will therefore attract the male wasp dabbing a spot of pollen on his tail. Flowers are very specific about using their pollen much like delivering letters.

Banksia flowers have evolved to attract birds and provide a perch, pollen and insects. The pollen goes on the bird’s face and head. The flowers are densely packed so that they are not attractive to insect pollination. The fascinating thing about flowers is that depending on what flower the bird is attracted to, depends on where the flower will deposit its pollen on the bird. Michael said it was entirely possible that a Dryandrawill deposit its pollen on the bird’s head while Anigozanthospollen will be deposited on a bird’s back. Other plants may deposit their pollen on the breast so that the bird can virtually carry different pollens all over its body from many different plants.

Mammals such as the Honey Possum with its long snout will pollinate flowers as well as Fairy Gliders and Dibblers (a native rat which was presumed extinct for 83 years until it was rediscovered in 1967).

http://www.michaelmorcombe.com.au/dibblerstory.html

Sandpaper Wattle, Acacia denticulosa

Among the hundreds of species of Acacia, Acacia denticulosa, Sandpaper Wattle, is one of the most striking. The species was first collected near Mt Churchman by Jesse Young, a member of Ernest Giles’ expedition across the Great Victoria Desert in 1875. Young (1852–1909) was the astronomer and principal plant collector (assisted by William Tietkens). With the consent of Thomas Elder, sponsor of the expedition, he passed his specimens to Ferdinand Mueller, Government Botanist of Victoria (remember, there was no botanist in WA then). The collection totalled about 400 species, of which some 63 were new. Mueller named many of these, including this species, published in 1876. The name refers to the toothed margins of the phyllodes but perhaps the more unusual feature of these is the very rough surface from which the common name is derived. This is due to short, conical outgrowths with gland-like tips that are scattered over the lamina and edges of the phyllodes. The phyllodes and young branchlets (also rough at this stage) are slightly sticky.

In the wild the plant is a shrub up to 4 m tall (bottom left) but in the garden it grows to 6 m and can spread to 8 m wide (bottom left). It has an open, rather ungainly habit. Its bark is almost smooth, pale greyish brown, or brown when wet (bottom right). In full flower the tree appears covered with large, golden, woolly caterpillars (centre left).

I bought my plant as a small seedling in April 2008. It grew quickly and by August 2010 was already 3 metres tall. Since 2010 it has flowered well, starting in July and continuing to the end of August. One reason for its colourful show is that it usually has several spikes per axil. They have a faint ‘wattle’ scent. The fruit is relatively inconspicuous, being a narrow, undulating pod up to 7.5 cm long and 3–4 mm wide, holding small, dark brown shiny seeds (centre right).

The species has no close relatives. The plant has no lignotuber, hence is killed by fire and regenerates from seed. Given adequate space it does not require pruning. Should this be necessary it should be done progressively as the plant grows, never cutting below the foliage.

Sandpaper Wattle is rare in the wild, known mainly from granite outcrops from near Mt Churchman south-east to Nungarin, with a record near Wongan Hills. It is a Declared Rare Flora (Threatened). Like another rare species from granite rocks, Eucalyptus caesia, it is proving amenable to cultivation. A plant in the garden of the previous WA Herbarium grew to a large size.

-Alex George

Photos by Alex show the habit, bark, flowers and young pods.

References

Brooker, Lesley (2015), Explorers Routes Revisited: Giles 1875 Expedition, Hesperian Press, Carlisle.

Maslin, B.R. & Cowan, R.S. (2001), Acacia denticulosa F.Muell. in A.E.Orchard & A.J.G.Wilson (eds), Flora of Australia 11A: 238, 368, 370, 481, ABRS, Canberra, & CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Coming Events

Christmas wildflower walk

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed sed lacus et neque consequat euismod at ac odio. Vestibulum viverra urna orci, elementum dignissim sapien interdum vestibulum.

Read more2014 Albany Wildflower Exhibition

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed sed lacus et neque consequat euismod at ac odio. Vestibulum viverra urna orci, elementum dignissim sapien interdum vestibulum.

Read more2014 Albany Society

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed sed lacus et neque consequat euismod at ac odio. Vestibulum viverra urna orci, elementum dignissim sapien interdum vestibulum.

Read moreAnother Event 01

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed sed lacus et neque consequat euismod at ac odio. Vestibulum viverra urna orci, elementum dignissim sapien interdum vestibulum.

Read moreAnother Event 02

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed sed lacus et neque consequat euismod at ac odio. Vestibulum viverra urna orci, elementum dignissim sapien interdum vestibulum.

Read moreAnother Event 03

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed sed lacus et neque consequat euismod at ac odio. Vestibulum viverra urna orci, elementum dignissim sapien interdum vestibulum.

Read moreComing Events

Coming Events

AGM Friday 22nd November 7pm

22 November @ 7:00 pm

Please join us for our AGM. All positions on the committee will be declared vacant. Review what happened in 2024. […]

Read moreStar Swamp Bushland Reserve Guided Walk

23 November @ 8:00 am

Join David Pike for a 90 minute guided walk through the Star Swamp Bushland, looking at flora, insects and wildlife. […]

Read morePropagation Group

25 November @ 12:00 pm

This group meets on the third Monday of the month to propagate plants from seeds and cuttings. Knowledge is shared; […]

Read more“The Problem with Myrtle Rust” with Dr Anna Hopkins

26 November @ 7:30 pm

Join Northern Suburbs members for the monthly meeting, at the Henderson Environment Centre, Groat St North Beach, starting at 7.30pm. […]

Read moreTrigg Bushland Reserve Guided Walk

30 November @ 8:00 am

Join David Pike and Mitch Polain for a 2 hour guided walk in Trigg Bushland Reserve, looking at flora, insects […]

Read moreLandsdale Conservation Park Guided Walk

7 December @ 8:00 am

Join David Pike for a 90 minute guided walk in Landsdale Conservation Park, looking at flora, insects and wildlife. Meet […]

Read moreThe Wildflower Society uses its independent technical knowledge of WA’s wildflowers to help you better know, grow, enjoy and conserve the wildflowers of Western Australia.

We are committed to providing help to the following…